International Conference of Asian Food Study 2013

‘The Meanings of Cookery: Everyday Life and Aesthetics in Meiji Japan'

Tomoko Tamari

This paper was presented in October 2013 at the International Conference of Asian Food Study, Zhejiang Gongshang University, Shaoxing, China. It appeared in The Proceedings of 2013 Shaoxing Asian Food Study Conference, ‘Health and Civilization’ 2014, pp 467- 480.

Abstract

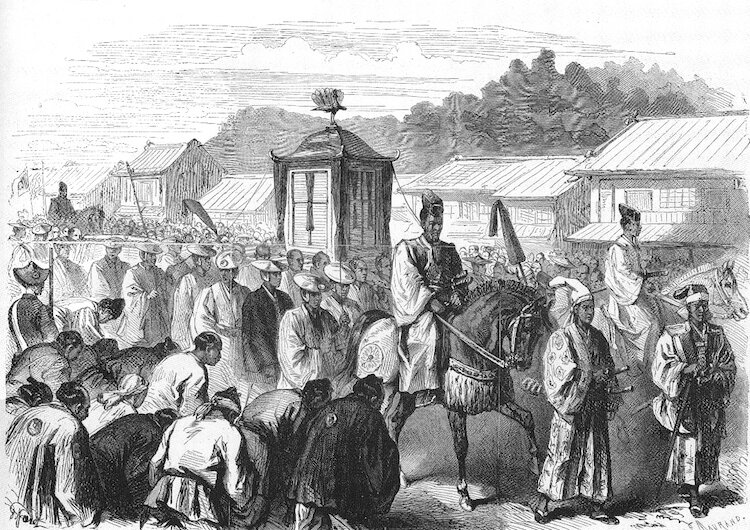

The aim of the paper is to explore the emergence of new women’s domestic narratives of cooking and modern family life which accompanied the growth of consumer culture in Japan. Japanese haute cuisine had been largely produced by professional chiefs who via the patriarchal apprentice system, but began to be democratized in the late nineteenth century. The first Japanese cooking school started in 1882 attracted the higher class women. Cooking began to be seen as a prestigious form of knowledge and status symbol. Around 1887, the influential Meiji reformers and other intellectuals presented the modern family as a sanctuary based on greater intimacy between the couple with the emphasis on the home (houmu or Katei) as opposed to the patriarchal conservative family system (ie). Women became seen as the domestic managers of modern family life with the key duty to produce and maintain healthy citizens, which fitted into the national project. In this sense, cooking become designated as scientific and rational, a part of women’s domestic practice. With the growth of urbanization and industrialization in the 1900s, the new middle class modern family become presented as the ideal consumption unit. At the same time, the expanding commercial women’s magazines started to provide, not only new recipes, but also new knowledge about aspects of food culture and lifestyle. Cooking became commercialised and popularized as systematised domestic knowledge as well as being seen as a form of home entertainment as part of a new consumer lifestyle. I will explore the relationship between wider social and cultural change and the configuration of cooking discourses in order to illustrate how cooking as a domestic banal practice and set of experiences was re- and de-contexualised in the wake of the Meiji Restoration, and the development of consumer culture and the emergence of domestic and vernacular aesthetic sensitivities late 19th century Japan.